Servant Leadership, Engagement, and Employee Outcomes: The Moderating Roles of Proactivity and Job Autonomy

[El liderazgo de servicio, la implicaciĂłn y los resultados de los empleados: roles moderadores de la proactividad y de la autonomĂa en el puesto]

Dana Yagil and Ravit Oren

University of Haifa, Israel

https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a1

Received 25 March 2020, Accepted 27 November 2020

Abstract

This paper presents a moderation-mediation model suggesting that proactivity and job autonomy moderate the mediating effects of engagement on the relationship of servant leadership with job performance and lateness. Data were collected from a sample of 50 bank departments from three sources: managers (n = 50), employees (n = 165), and objective data provided by human resources departments. The results show that as expected, the association of servant leadership with work engagement was stronger for employees with low levels of proactivity and job autonomy. Proactivity moderated the mediating effect of engagement on the relationship of servant leadership with both job performance and lateness; autonomy moderated the mediating effect of engagement on the relationship between servant leadership and lateness. The results imply that placing employees with low levels of proactivity and job autonomy under the supervision of servant leaders can engender higher job engagement and better organizational outcomes.

Resumen

El artículo presenta un modelo de moderación-mediación que indica que la proactividad y la autonomía en el puesto de trabajo moderan los efectos mediadores de la implicación en la relación del liderazgo de servicio con el desempeño e impuntualidad de los empleados. Se recogieron datos de una muestra de 50 departamentos bancarios procedentes de tres fuentes: directivos (n = 50), empleados (n = 165) y datos objetivos facilitados por los departamentos de recursos humanos. Los resultados muestran que, tal y como se esperaba, la asociación del liderazgo de servicio y la implicación en el trabajo era mayor en los empleados con baja proactividad y autonomía en el puesto. La proactividad moderaba el efecto mediador de la implicación en la relación del liderazgo de servicio con el desempeño y la impuntualidad. La autonomía moderaba el efecto mediador de la implicación en el puesto en la relación entre el liderazgo de servicio y la impuntualidad de los empleados. Los resultados indican que poner a los empleados con bajo nivel de proactividad y autonomía en el puesto bajo la supervisión de líderes servidores puede mejorar la implicación en el puesto y los resultados organizativos.

Palabras clave

Liderazgo de servicio, ImpliciĂłn en el puesto, Proactividad, AutonomĂa en el puesto, Desempeño, ImpuntualidadKeywords

Servant leadership, Engagement, Proactivity, Job autonomy, Performance, LatenessCite this article as: Yagil, D. and Oren, R. (2021). Servant Leadership, Engagement, and Employee Outcomes: The Moderating Roles of Proactivity and Job Autonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(1), 59 - 68. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a1

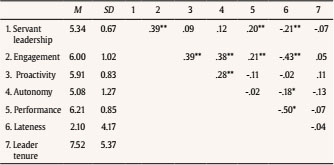

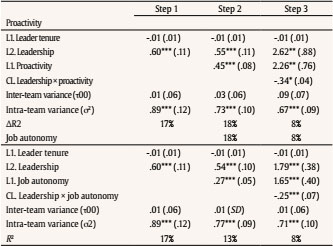

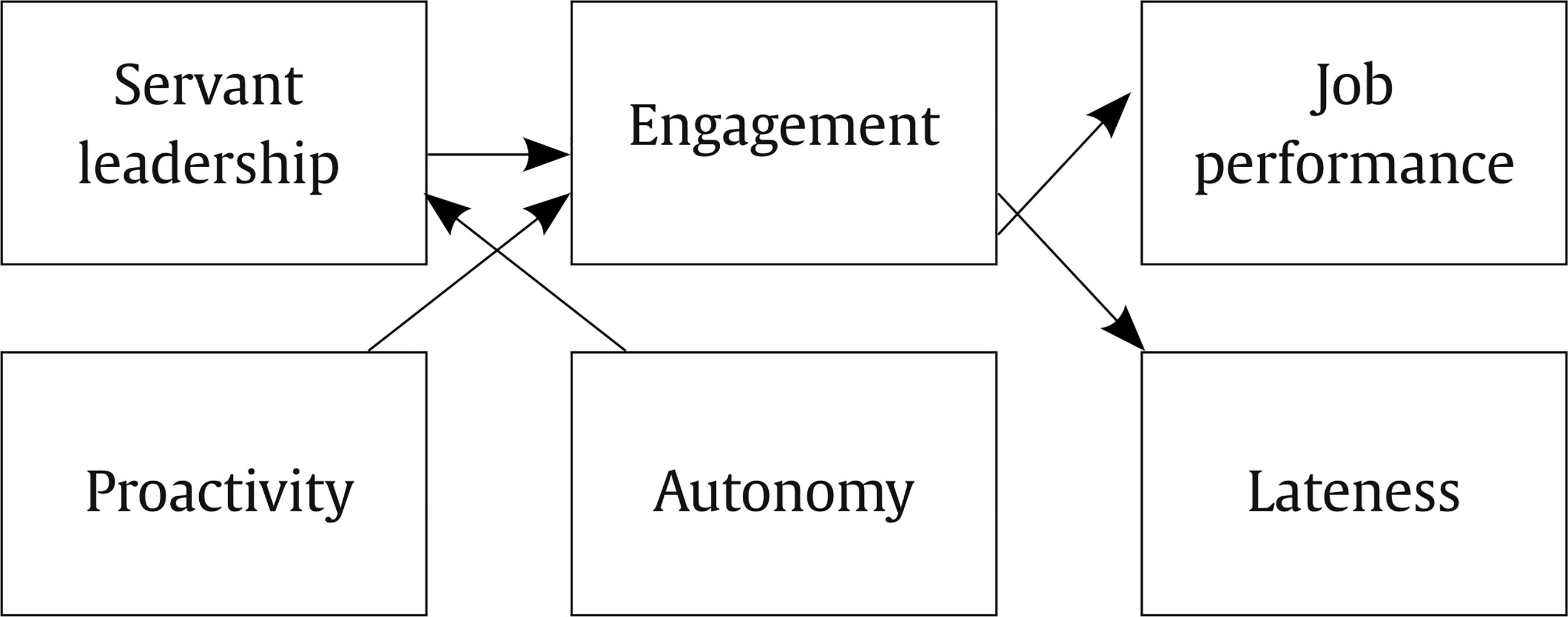

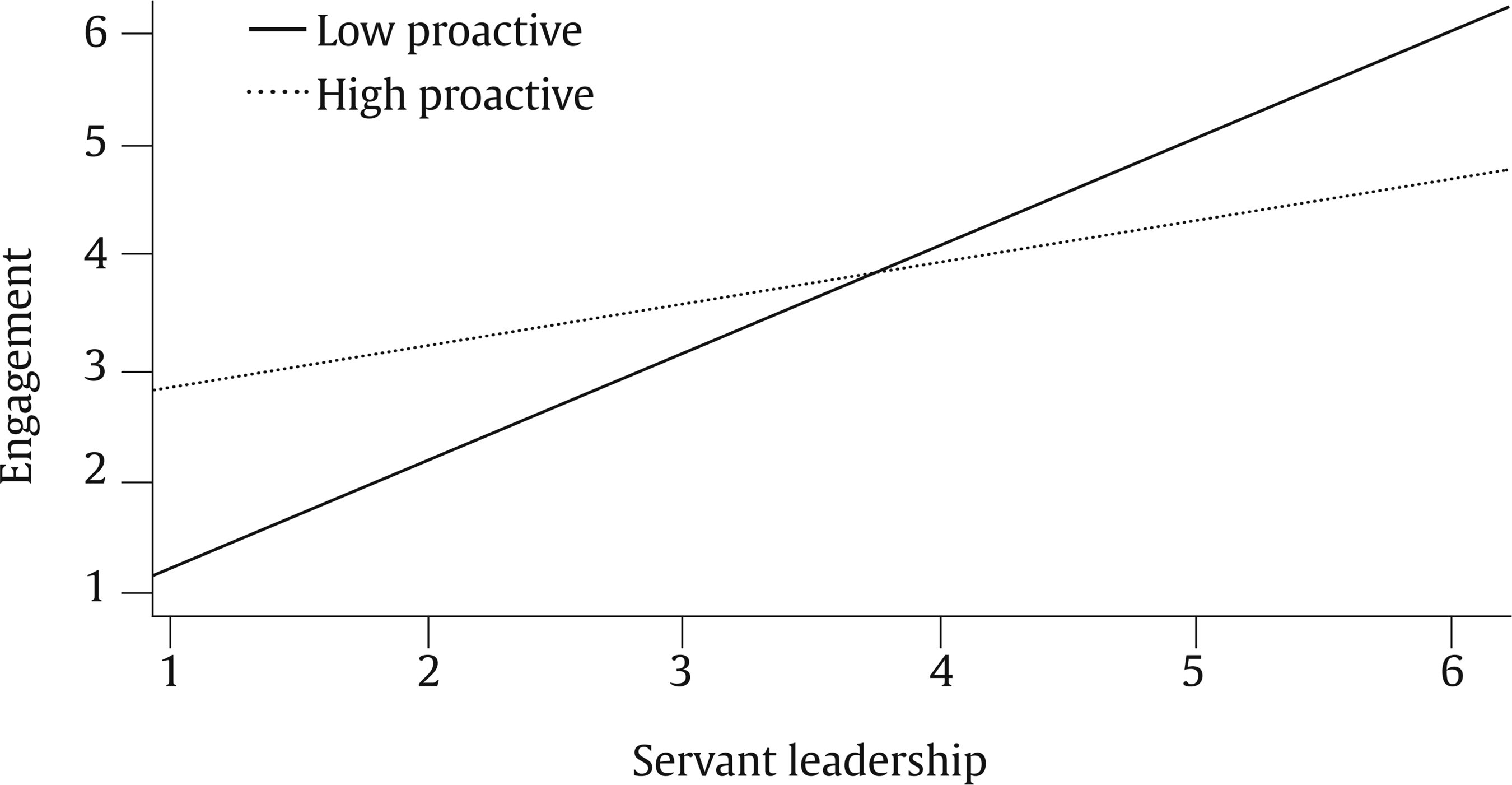

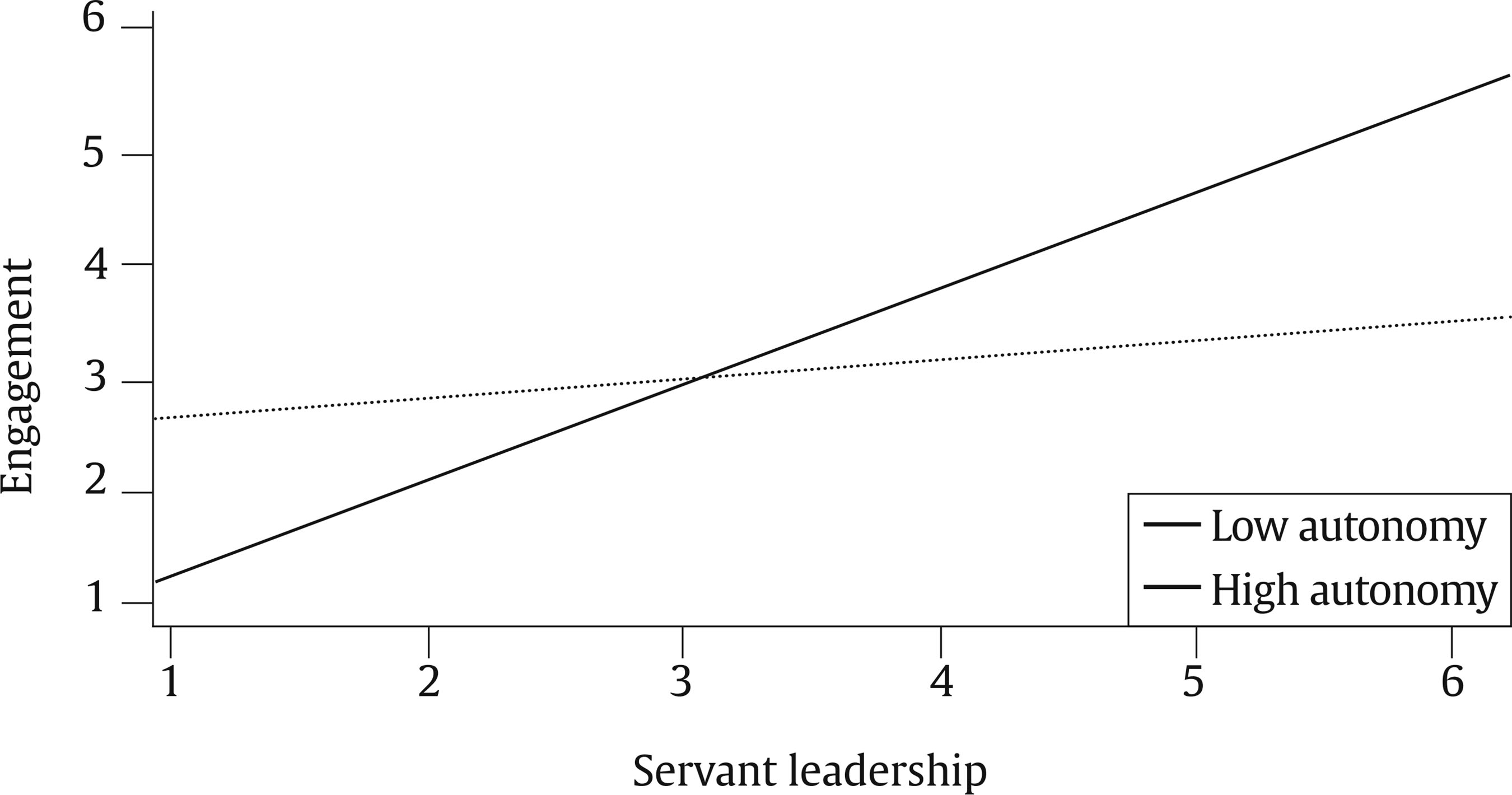

dyagil@research.haifa.ac.il Correspondence: dyagil@research.haifa.ac.il (D. Yagil).Servant leadership is characterized by a focus on followers’ growth and empowerment (Greenleaf, 1977, 1998; Liden et al., 2008). Servant leaders act as role models by providing support, behaving ethically, and caring for the community (Newman et al., 2017). Research indicates that servant leaders promote organizational functioning (Greenleaf, 1977; Liden et al., 2014; Parris & Peachey, 2013), as reflected in outcomes such as enhanced employee performance (e.g., Chiniara & Bentein, 2016; Liden et al., 2008, 2014; Peterson et al., 2012; van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015) and a low level of turnover intentions (Hunter et al., 2013). However, improving performance is not the first priority of servant leaders; compared with other leadership styles, servant leadership is unique in that the leader is primarily interested in satisfying followers’ needs (Greenleaf, 1977, 1998; Liden et al., 2008; van Dierendonck, 2011). Servant leadership is related to work engagement (Bao et al., 2018), a desirable condition (Macey & Schneider, 2008) associated with outcomes such as high organizational commitment (Richardsen et al., 2006) and low turnover intentions (Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Yet, relatively little research has explored the mediating role of engagement (De Clercq et al., 2014) in the relationship between leadership and outcomes. Exploring the relationships among servant leadership, engagement, and outcome variables can enhance our understanding of the mechanisms that enable servant leaders to affect their followers’ performance and counterproductive behavior. The present study also aimed to contribute to understanding the impact of servant leaders on employee engagement by considering the perspectives of the moderating effects of employees’ personality (i.e., proactivity) and work conditions (i.e., job autonomy). A key driver of proactive work performance is self-perceived capability to perform activities that extend beyond prescribed tasks (Zhang et al., 2016). Because a sense of self-efficacy is crucial for work engagement (Bakker et al., 2008; Xanthopoulou et al., 2009), less proactive individuals tend to be less engaged, more passive, and react to rather than initiating events. Furthermore, because non-proactive employees are less conducive to the organization’s purposes, they might receive fewer resources than their more proactive counterparts, and consequently feel disoriented and disengaged (Shuck et al., 2016). We suggest that the unique qualities of servant leadership might be especially valuable for low-proactivity employees in affecting engagement and related outcomes. Additionally, to the best of our knowledge, no prior studies have examined the influence of job characteristics on the servant leadership-engagement relationship. However, contingency models of leadership indicate that leaders’ impact on followers depends on, among other things, work context characteristics, such as task structure (Fiedler, 1964). Job autonomy is considered one of the most important features of work design, affecting employees’ feeling of empowerment and sense of responsibility to the job (Hackman & Oldham, 1976). Although leaders might not be able to influence inherent job characteristics that engender low autonomy, servant leaders could possibly increase the engagement of employees with low job autonomy by enhancing their sense of psychological autonomy. Leaders frequently operate in situations where fundamental conditions for engagement are missing or out of their control—such as when employees’ personality includes a low level of proactivity or the nature of the job prescribes a low level of autonomy. A third contribution of the present study is its examination of the novel notion that servant leaders, who emphasize employees’ needs above all (Greenleaf, 1970; van Dierendonck, 2011), can promote engagement even under less-than-ideal conditions, namely, low proactivity and employees with low job autonomy. By testing the notion that leaders can promote engagement even under such constraining conditions, this study enhances our understanding of the unique impact of the servant leadership style. A fourth contribution is the exploration of outcome variables in relation to lateness. Withdrawal behaviors have received little attention from scholars of servant leadership (Hunter et al., 2013). To test the notion that a servant leader’s effectiveness is manifested not only in the promotion of constructive behaviors, but also in the reduction of counterproductive behaviors (Holtz & Harold, 2013), we explored the relationship between servant leadership and employee lateness, measured by objective documentation of employee behavior. Employee engagement, which is enhanced by servant leadership (De Clercq et al., 2014), is expected to be negatively related to lateness, because engaged employees are physically and psychologically able to invest themselves fully in their work roles (Kahn, 1990) and engage in fewer withdrawal behaviors (Volpone & Avery, 2013). From a practical perspective, we examined how organizations promote engagement under a variety of conditions through leadership. Organizations with jobs that do not offer much autonomy to employees might particularly benefit from training managers in servant leadership. We tested a moderation-mediation model suggesting that proactivity and job autonomy moderate the mediating effect of engagement on the relationship of servant leadership with job performance and lateness. Survey data were collected from managers and employees, alongside objective data provided by human resources departments. The research model is presented in Figure 1. Literature Review Servant Leadership, Work Engagement, and Employee Outcomes Servant leadership is positively associated with important outcomes such as employees’ organizational commitment and in-role performance (e.g., Chiniara & Bentein, 2016; Liden et al., 2008, 2014; Peterson et al., 2012; van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2014) and negatively associated with disengagement and turnover intentions (Hunter et al., 2013). This positive impact of servant leaders is explained by leaders’ focus on the satisfaction of followers’ needs. Employees tend to reciprocate a leader’s concern for satisfying their needs by demonstrating high-level performance, which contributes to the leader’s well-being and goal achievement. Additionally, because servant leaders prioritize followers’ growth, they enable them to assume new responsibilities and develop new skills, thereby contributing to enhanced performance (Chiniara & Bentein, 2016). Work engagement is a core motivational construct and an antecedent of employees’ personal and work-related outcomes, characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption (e.g., Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Engagement is conceptually associated with leadership because a primary function of leadership is to instill motivation and meaning in employees (Macey & Schneider, 2008). Specifically, servant leadership is primarily built on the value of serving the employees (Greenleaf, 1970; Mayer et al., 2008; van Dierendonck, 2011; van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015). Servant leaders stimulate work engagement by creating an environment that promotes psychological safety—employees’ sense that their work situation is not threatening, which empowers them to give their utmost at work. Servant leaders’ appreciation of followers’ contributions to the organization, along with their inclination to empower followers, also contributes to followers’ motivation and a sense of meaning in their work (De Clercq et al., 2014). Engagement is further promoted through the satisfaction of followers’ needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, 2000; van Dierendonck et al., 2014). A major characteristic of servant leaders, their explicit focus on followers’ need satisfaction, can be expected to lead them to recognize employees’ needs and contribute to their fulfillment through empowerment, provision of opportunities to develop skills, and caring (Liden et al., 2008). A work environment that allows employees to feel competent, volitional, and related to others at work, promotes autonomous motivation, which involves engaging freely in a job for inherent satisfaction or through identifying with the value or meaning of work (Meyer & Gagne, 2008). Thus, satisfying needs promotes employee work engagement (Trépanier et al., 2015). Research has demonstrated a relationship between work engagement and job performance (e.g., Barrick et al., 2015; Demerouti & Cropanzano, 2010). The positive and active state of mind that characterizes engaged employees motivates them to work hard and perform well. Due to this state, engaged employees approach their work proactively (Salanova & Schaufeli, 2008), are more dynamic, are more responsive to new information, and work harder (Bakker & Leiter, 2010). Engaged employees are also likely to show more positive and less deviant work behaviors. The energy produced by engagement encourages activity and productive work behavior. Because engaged employees are highly dedicated to their work, they can be expected to avoid or reduce activities that might damage their work, such as counterproductive work behaviors (Sousa & van Dierendonck, 2017). Thus, through their emphasis on followers needs and the support, encouragement, and empowerment of followers, servant leaders enhance the positive motivational state of engagement, which contributes to job performance and inhibits withdrawal behaviors. We suggest that these indirect relationships of servant leadership with performance and lateness through engagement are moderated by employee proactivity and job autonomy. Employee Proactivity A proactive personality refers to a behavioral tendency to identify and act on opportunities to enact change (Crant, 2000). In the workplace, a proactive personality manifests in employees’ searching for ways to improve work processes and investing in skill development. By contrast, less proactive employees are more inclined to react to, adapt to, and be shaped by their environments (Bakker et al., 2012). Bauer et al. (2019) suggested that because proactivity and servant leadership provide similar benefits such as receiving support and finding meaning in a job, they might substitute for each other. Thus, in instances in which servant leadership is high, there is less need for proactivity. In a study on newcomers to an organization, the authors found that servant leadership was related to a reduction in the necessity of proactivity on the part of employees, by providing a rich environment in which adjustment takes place. Accordingly, servant leaders might have less impact on the engagement of highly proactive employees than the engagement of less proactive employees. For example, servant leaders’ enhancement of employee engagement through increasing resources and mitigating demands (Sousa & van Dierendonck, 2017) can be expected to be less significant for highly proactive employees, who tend to actively change their own environment by seeking resources (Bakker et al., 2012), than for less proactive employees, who tend to accept their environment rather than change it and are consequently less involved in initiatives designed to maximize resources and skill development. Thus, we suggest that the unique qualities of servant leadership might be especially valuable for low-proactivity employees in affecting engagement and related outcomes. Hypothesis 1a: The relationship between servant leadership and engagement will be stronger when employees’ proactivity is low compared with when it is high. Hypothesis 1b: The indirect relationship of servant leadership with job performance and lateness through engagement will be stronger when employees’ proactivity is low compared with when it is high. Job Autonomy Job autonomy has been identified as one of the most important features of work design. High job autonomy involves high levels of discretion when making job-related decisions, such as task performance methods, choosing which procedures to follow, and work scheduling (Ng et al., 2008). High job autonomy enhances employees’ feeling of empowerment and increases their sense of responsibility to their job (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), whereas low control at work can engender a passive and helpless approach toward work (Frese, 1989). Leaders might not be able to influence inherent job characteristics that engender low autonomy, but servant leaders could possibly increase the engagement of employees with low job autonomy by enhancing their sense of psychological autonomy. Servant leadership is characterized by empowerment, reflected in the provision of bounded discretion in decision making, sharing information, and encouraging employees to suggest ideas for improvement (Greenleaf, 1977; van Dierendonck, 2011). Another characteristic of servant leadership is accountability—holding employees accountable for performance outcomes they can control and providing them responsibility for outcomes (van Dierendonck, 2011). Such leadership behaviors can be expected to be more valuable for employees with low job autonomy because their job design limits opportunities for decision making or assuming significant responsibility. Thus, we predicted that the impact of servant leadership will be stronger under conditions of low levels of job autonomy. Hypothesis 2a: The relationship between servant leadership and engagement will be stronger when job autonomy is low compared with when it is high. Hypothesis 2b: The indirect relationship of servant leadership with job performance and lateness through engagement will be stronger when job autonomy is low compared with when it is high. Sample and Procedure The study was conducted in branches of a large Israeli bank, featuring about 100 branches throughout the country. The choice of branches was based on their accessibility; that is, receiving the necessary permission to conduct the study from the banks’ branch managers. Thirty-two branch managers were approached, with the intention of recruiting a variety of branches in terms of size (between 13 workers in the smallest branches up to about 100 in the larger ones) and geographic areas. Twenty-five branch managers (78% of those approached) agreed to have the study conducted in their branches. In the 25 branches, we approached 68 department managers, 50 of whom (73.5%) gave their consent. Of the 50 departments included in the study, 28 departments were related to personal or private banking, 16 to business banking, four to mortgage banking, and two to general banking. Of 242 questionnaires administered at two points to all workers in the departments whose managers agreed to participate in the study, 165 were returned (a 68.2% response rate at both time points). In our sample, 59.4% of the employees were female, the average age was 43.6 (SD = 10.34), the average total years of education was 14.26 (SD = 1.47), and the average tenure in the bank was 10.4 years (SD = 8.73). Regarding the managers, 34% were female, the average age was 46.98 years (SD = 8.57), the average total years of education was 15.32 years (SD = 1.74), and the average tenure in the bank was 7.52 years (SD = 5.37). To reduce single-source bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), employees completed questionnaires at two points. First, employees received the servant leadership questionnaire, along with a cover letter, which explained the purpose of the study, described the survey process, and assured confidentiality and the voluntary nature of the study. About 2 weeks later, employees completed questionnaires relating to engagement, autonomy, and proactivity. To ensure confidentiality, respondents placed their completed questionnaire in a sealed envelope, which was then collected by a research assistant. The research assistants had a list of all employees’ names. Each employee who completed the first questionnaire received a number on both the list and the questionnaire. The same number was also written on the questionnaire distributed during the second administration. Employees were also asked to report, at both time points, identifying personal information (e.g., mother’s maiden name) to further ensure that the matching of the questionnaires was correct. This procedure ensured that employees’ names were kept separate from the questionnaires to prevent the possible identification of respondents by individuals outside the research team. At Time 2, managers provided performance evaluations and branch human resources managers provided lateness data for each employee who participated in the study. Measures We collected data from three sources: employees’ self-reports about servant leadership, engagement, job autonomy, and proactivity; managers’ evaluations of employee performance; and data regarding lateness documented by human resources departments. Time 1 Servant leadership. We measured servant leadership perceptions using the 30-item Servant Leadership Survey (Van Dierndonck & Nuijten, 2011). A sample item is: “My manager emphasizes the importance of focusing on the good of the whole.” The response scale ranged from 1 (to a minimal extent) to 7 (to a very high extent). The measure has reasonable convergent validity and indicated by Cronbach’s alpha reliability = .97, composite reliability (CR) value = .79, and average variance extracted (AVE) = .50. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the Fornell-Larcker criterion. The square root value of the AVE of the scale (.71) is greater than the correlations of the scale with the other scales (correlations are presented in Table 1). Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations   Note. The correlations are presented at the individual level (n = 165). *p < .05, **p < .01. Servant leadership was aggregated for several reasons. First, the aggregated variable reduced the possible biasing effect of the individual level, such as single-source bias (Hunter et al., 2013; Leroy et. al., 2015). Furthermore, Liden et al. (2008) maintained that “servant leadership aggregated to the group-level relates to individual outcomes because the pervasiveness with which leaders engage in servant leader behaviors across all followers in their work groups influences each individual in that work group to be more committed to the organization, to perform at higher levels” (p. 164). In other words, individual group members’ attitudes and behaviors are influenced not only by their own relationships with the leader, but also by their view of how the leader treats other group members. Thus, aggregated servant leadership captures the overall treatment of group members, and followers will respond more positively in terms of attitudes and behaviors when they sense that others are treated fairly (Liden et al., 2008). Tests of the possibility to aggregate this variable showed that aggregation was justified for servant leadership: rwg = .87, ICC(1) = .37, ICC(2) = .66 (Biemann et al., 2012). Time 2 Work engagement. Engagement was measured using the 9-item UWES-9 questionnaire (Schaufeli et al., 2006), which is based on Schaufeli and Bakker’s (2004) UWES questionnaire. The measure consists of three subscales: vigor (sample item: “At my work, I feel bursting with energy”), dedication (sample item: “I am enthusiastic about my job”), and absorption (sample item: “I feel happy when I am working intensely”). The response scale ranged from 1 (almost never) to 7 (very often). Exploratory factor analysis resulted in one factor explaining 60.8% of the variance. Cronbach’s alpha reliability = .91, CR value = .93, and AVE = .61. The square root value of the AVE of the scale (.78) is greater than the correlations of the scale with the other scales. Based on the high reliability, the analyses were conducted with a single scale featuring all items. Autonomy. We measured autonomy using the 9-item Work Autonomy Scale (Breaugh, 1999), which measures employees’ perceptions regarding their control over their work performance. The scale addresses three facets of autonomy: method autonomy (sample item: “I am allowed to decide how to go about getting my job done [the methods to use]”); scheduling autonomy (sample item: “I have control over the scheduling of my work”); and criteria autonomy (sample item: “My job allows me to modify the normal way we are evaluated so that I can emphasize some aspects of my job and play down others”). The response scale ranged from 1 (almost never) to 7 (very often). Exploratory factor analysis resulted in three factors corresponding to scheduling autonomy (explaining 30.05% of the variance), method autonomy (explaining 24.53% of the variance), and criteria autonomy (explaining 19.50% of the variance); together, the factors explained 74.08% of the variance. Cronbach’s alpha reliability = .86, CR value = .81, and AVE = .61. The square root value of the AVE of the scale (.84) is greater than the correlations of the scale with the other scales. Based on the high reliability, the analyses were conducted with a single scale featuring all items. Proactive personality. We measured proactivity using Seibert et al.’s (1999) 10-item scale, which is based on Bateman and Crant’s (1993) Proactive Personality Scale. A sample item is: “I can spot a good opportunity long before others can.” The response scale ranged from 1 (to a minimal extent) to 7 (to a very high extent); Cronbach’s alpha reliability = .87, CR value = .84, and AVE = .52. The square root value of the AVE of the scale (.72) is greater than the correlations of the scale with the other. Job performance. Performance was measured using Williams and Anderson’s (1991) 7-item scale, used by managers to evaluate the extent to which employees follow the formal requirements of their job. A sample item is: “Adequately completes assigned duties.” The response scale ranged from 1 (to a minimal extent) to 7 (to a very high extent); Cronbach’s alpha reliability = .91, CR value = .93, and AVE = .81. The square root value of the AVE of the scale (.90) is greater than the correlations of the scale with the other. Lateness. Data regarding employees’ lateness were extracted by human resources managers in the various branches from the bank’s time-tracking system. Managers provided data regarding each employee’s lateness during the 2 months preceding the administration of the questionnaires. The questionnaires were translated into Hebrew and then back into English until a full match was achieved (Brislin et al., 1973). Control variables. We collected data about several potential control variables, such as leaders’ and followers’ age, gender, tenure, and education. However, none of these variables correlated with the dependent variables. Recommendations regarding criteria for inclusion of control variables (Becker et al., 2016; Bernerth & Aguinis, 2016; Carlson & Wu, 2012) suggest that only variables that correlate with dependent variables or are theoretically important should be included in the model. Accordingly, we included leader tenure in the analysis because the emotional impact of s leader on followers, which is highly relevant in the predictions of the present study, is expected to increase with time (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). Analyses conducted without this control variable did not change the pattern of the results. Analytic Strategy and Preliminary Analyses Employees in our sample were grouped in their departments, each headed by a manager. To model this nested nature appropriately, we used hierarchical linear modeling with the PROC MIXED procedure in SAS. Analyses were conducted at the individual level (engagement, proactivity, job autonomy, job performance, and lateness; n = 165) and the group level (servant leadership; n = 50; Bliese & Hanges, 2004). Predictors were grand-mean centered (Aiken et al., 1991). Regarding the first-stage moderation (Hypotheses 1 and 2), we conducted regression analyses. Leader tenure (the control variable) was entered in the first step, servant leadership and the moderator in the second step, and the interaction term in the third step. We used multilevel simple slope analysis (Preacher et al., 2006) to estimate the simple slopes at high and low levels of the moderators. To examine the moderated indirect effects (Hypotheses 1a and 2a), the RMediation package (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011) was used, based on the hierarchical linear modeling statistical framework (Tingley et al., 2014). We calculated confidence intervals of mediation effects based on 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011), separately for low (mean – 1 SD) and high (mean + 1 SD) levels of moderation. Confidence intervals not including zero represent evidence of significant mediation. Before testing our hypotheses, we ran confirmatory factor analyses to explore the factorial structures of the measures. Our model, which included the five variables measured with questionnaires, showed acceptable fit, χ2(1,282) = 2,042, p < .001; CFI = .93; TLI = .88; RMSEA = .05. We applied a single-factor model, with all items loaded on one factor. However, the fit indexes of the five-factor model were significantly better than those of the single-factor model: Δχ2(157) = 818.267, p < .001; CFI = .86; TLI = .80; RMSEA = .07. To test for possible common-method bias, we used Harman’s single-factor test, entering all items comprising the scale in a principal component factor analysis. The analysis resulted in 14 distinct factors accounting for 74.38% of the total variance. The first unrotated factor captured only 25.78% of the variance in data. Because no single factor emerged and the first factor did not capture most of the variance, the results suggest that CMV was not an issue in this study (Tehseen et al., 2017). Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the variables and Table 2 summarizes the results regarding the moderating effect of proactivity and job autonomy on the relationship between servant leadership and engagement. Table 2 The Moderating Effects of Proactivity and Job Autonomy in the Relationship between Servant Leadership and Engagement (SE presented in parentheses)   Note. L1 = level 1; L2 = level 2; LC = cross level *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001 The results indicate that servant leadership was related positively to performance (β = .31, p < .01) and negatively to lateness (β = -2.35, p < .01). The results also show a significant interaction effect of servant leadership and proactivity with engagement (β = -.34, SE =.14, p < .01). We calculated the simple slopes and plotted the interaction effect in Figure 2. In support of Hypothesis 1a, the simple regression slope for leadership on engagement was significantly steeper under low proactivity (β = .92, SE =.19, p < .001) than under high proactivity (β = .35, SE = .13, p < .05). In support of Hypothesis 1b, the indirect effect of servant leadership on performance via engagement was stronger when proactivity was low (indirect effect = .16, 95% CI [.03, .34]) than when proactivity was high (indirect effect = .06, 95% CI [.00, .15]). The indirect effect of servant leadership on lateness via engagement was also stronger when proactivity was low (indirect effect = -1.44, 95% CI [-2.45, -.67]) than when proactivity was high (indirect effect = -.58, 95% CI [-1.09, -.15). The relationships of engagement with performance and lateness were β = .18 (p < .05) and β = -1.57, (p < .01), respectively. The results presented in Table 2 and Figure 3 show a significant interaction effect of servant leadership and autonomy on engagement (β = -.25, SE = .07, p < .01). A simple slope analysis supported Hypothesis 2a, showing that the relationship between servant leadership and engagement was significant under low autonomy (β = .84, SE = .10, p < .001), but not under high autonomy (β = .18, SE = .14, ns). Contrary to expectations, the indirect effect of servant leadership on performance via engagement was not significant, both when job autonomy was low (indirect effect = .08, 95% CI [-.04, .22]) and high (indirect effect = .02, 95% CI [-.01 .08]). The indirect effect of servant leadership on lateness via engagement was significant when job autonomy was low (indirect effect = -.88, 95% CI [-1.52,-.32]), but not significant when autonomy was high (indirect effect = -.17, 95% CI [-.54, .12). In this model, the relationships of engagement with performance and lateness were β = .10 (ns) and β = -1.03, (p < .01), respectively. Hypothesis 2a was partially supported. This study contributed to the growing research on engagement and leadership by identifying boundary conditions related to employee characteristics or situational factors that determine when the positive impact of servant leaders is most pronounced. The results draw attention to leaders’ ability to transcend employees’ low proactivity and autonomy that restrict engagement. Our results demonstrate that the resources provided by servant leaders (Chiniara & Bentein, 2016; Greenleaf, 1970; van Dierendonck, 2011; van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015) are most important when employees’ personal or situational resources are limited (i.e., due to low proactivity or low job autonomy). By highlighting the mediating role of engagement, the results provide an explanation for how servant leaders influence employees with limited resources. However, the effect of servant leaders is contingent not only on the moderating conditions, but also on the outcomes in question. Although Newman et al. (2017) found that the indirect relationship of servant leadership with organizational citizenship behavior was higher among high-proactivity employees, our findings show that the effect of servant leadership on in-role performance and lateness was higher among low-proactivity employees. Thus, the moderating effect of proactivity on the relationship between servant leadership and outcomes might be different for extra-role behaviors and in-role behaviors. An additional contribution is related to the outcome variables tested in the study: job performance and lateness. Previous research has focused on servant leaders’ impact on productive behaviors, such as in-role performance and organizational citizenship behavior (van Dierendonck, 2011). We contributed to the existing knowledge about servant leadership outcomes by demonstrating the relationship between servant leadership and objective data on lateness behavior, which is associated with economic damage, increased stress, reduction of motivation among colleagues (Blau, 1994), absence, and quitting (Rosse, 1988). The results, thus, indicate that servant leaders do not just enhance positive attitudes and behaviors (e.g., van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2015), but may also inhibit employees’ counterproductive behaviors. Practical Implications Previous research on engagement offered generic practices designed to increase engagement across all types of jobs and employees’ needs (Macey & Schneider, 2008). Based on the results of this study, we suggest that beyond efforts to create the optimal conditions for engagement, consideration of employees’ personality and job characteristics should engender managerial practices designed to target the differential needs of employees. The results suggest that employees who are less engaged for personal or situational reasons should be supervised by servant leaders. Because leaders frequently cope with hindrances to employees’ engagement (Schmitt et al., 2016), learning how to increase engagement indirectly among employees experiencing limited personal and job-related resources is relevant to all leaders. Thus, training programs can include the qualities of servant leaders as guidelines for leadership development, emphasizing tailored solutions regarding the acceptance and provision of resources to employees, instead of the more conventional means of motivating employees. Consequently, the promotion of less proactive or less autonomous employees can be shared by various managers. Furthermore, servant leaders, who are inclined to mentor and empower their followers (van Dierendonck, 2011), might be especially effective in the management of millennials who reject authoritative leadership and instead expect leaders to perform a mentoring role and include employees in managerial decisions (Mukundan et al., 2013). Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research Some limitations of our study should be noted for future research. First, although we used multiple data sources, several variables were rated by employees simultaneously; thus, common-method bias could not be completely ruled out. However, we conducted a two-phase data collection process, and the measurement of servant leadership was separated in time from the measurement of the other variables, which reduced the threat of common-method variance (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition, the indirect effects of servant leadership on performance were not strong regarding both moderating variables: the difference between the two levels of proactivity was not large and the indirect effect was not significant at both levels of job autonomy. A possible explanation is that the performance scale used in the study (Williams & Anderson, 1991), which is unidimensional and addresses basic in-role duties (e.g., “Adequately completes assigned duties”), did not sufficiently capture the moderating impacts of proactivity and autonomy on the indirect effect of leadership on performance through engagement. It is desirable in future research to use performance evaluation scales that measure various performance dimensions (e.g., Hunt, 1996), which might highlight the moderated indirect effect of servant leaders on specific aspects of performance. Regarding the lack of a significant moderating effect of autonomy on performance, a possible explanation is that under a low level of autonomy, which might imply that performance is determined by the employee’s following of preset procedures (Wang & Cheng, 2010), the indirect impact of servant leaders on performance through engagement is minor. However, a low sense of autonomy might also result from temporary factors such as deadlines (Amabile et al., 1976) or employee standards (Stiglbauer & Kovacs, 2017). The measure we used to assess autonomy is correlated with actual autonomy (Breaugh, 1999) and has been interpreted as reflecting actual autonomy in previous studies (e.g., Den Hartog & Belschak, 2012), but we did not have an indicator of objective autonomy experienced by the employees in our study. Therefore, it is recommended that future research explore the moderating role of objective, rather than subjective, autonomy to identify the impact of this job characteristic. Leaders’ rating of employee performance was very high (mean = 6.21 on a scale of 1-7), suggesting that performance evaluation might be biased. As high means of servant leaders’ evaluation of followers’ performance were also found in other studies (e.g., Chiniara & Bentein, 2016; Liden et al., 2014; Stollberger et al., 2019), it is desirable to explore the relationship between servant leadership style and leader’s evaluation of followers’ performance. Although lateness was a dependent variable in the research model, data about lateness were gathered along with the measurement of the other variables, due to logistic considerations. However, because leaders had high tenure in their departments (a median of 4.5 years and a minimum of 8 months), leaders’ impact probably preceded the measured period of lateness, which referred to the last 3 months. Last, the study was conducted in only one type of organization—a bank—where autonomy might not have a profound impact on performance. Due to the sensitive nature of banking, employees’ actions are controlled by standardized regulations regarding decision-making procedures (Morris et al., 2008). Thus, the difference between high and low levels of job autonomy might have less influence on the outcome of performance than in other organizations. Furthermore, a sample drawn from a single type of organization could result in an unfavorable influence on the external validity of our conclusions and raise questions about generalizability. Thus, the use of various types of organizations would be a preferable alternative for future studies. We tested specific indicated barriers to engagement; future research should explore whether the findings can be generalized to other factors that might impair work experiences and performance, either associated with employee characteristics (e.g., a physical difficulty) or situational conditions (e.g., excessive job demands). The results suggest that servant leaders, who differ from other leaders in prioritizing the value of employees’ needs and well-being over personal and organizational considerations, are especially beneficial when employees experience inefficacy and low engagement. This, in turn, indicates that, paradoxically, outcomes might be enhanced when the leader accepts and supports employees, irrespective of their input. The results imply that in addition to fundamental practices designed to enhance employee engagement, differential practices should be considered as a means of promoting engagement among employees who experience a low level of efficacy. Placing these employees under the supervision of servant leaders and training leaders to develop servant leadership qualifications can engender higher job engagement and better organizational outcomes. Conflict of Interest The authors of this article declare no conflict of interest. Cite this article as: Dagil Y., & Oren R. (2021). Servant leadership, engagement, and employee outcomes: The moderating roles of proactivity and job autonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(1), 58-65. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a1 References |

Cite this article as: Yagil, D. and Oren, R. (2021). Servant Leadership, Engagement, and Employee Outcomes: The Moderating Roles of Proactivity and Job Autonomy. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 37(1), 59 - 68. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2021a1

dyagil@research.haifa.ac.il Correspondence: dyagil@research.haifa.ac.il (D. Yagil).Copyright © 2025. Colegio Oficial de la Psicología de Madrid

e-PUB

e-PUB CrossRef

CrossRef